(If at anytime you get bored, feel free to skip ahead to the two stories. Zero pressure.) Hi ya Corey, do hope you're enjoying a brilliant day! I looked through past resume pages here on my website and discovered two more articles for you to read - both are basically profiles, first of a famous artist, and next human research subjects. If after reading the three stories I emailed, plus these two, you feel you need more articles then just let me know and I'll be happy to provide more pieces. The introductory comments below in red were originally a part of the resume page that contained these two articles, among other things. I decided to keep them to help you get to know me professionally. And zero worries Corey, I know I won't be doing in-depth narrative features etc. if we decide we're a match, and that's more than fine with me. I have multiple outlets that buy my stories and the more diverse the mix of pieces I get to do the better. Also, I'd be honored to write about festivals etc. for one of your newspapers, yes indeed, a true honor. I sure do hope you like my stories! Cheers for now Corey! <smile>

Starting in earliest childhood, since primitive humans first grouped into clans - whether tribe members circling a fire inside a cave recess or a gaggle of modern-day listeners gathered around a radio - we're intrinsically drawn to, as well as societally and culturally defined by, illuminative and compelling storytelling.

Which is why I've always characterized myself professionally as a driven storyteller, versus a lazy fact-giver. An award-winning journalist unwilling to bore with easily composed but uninspired writing. No matter the topic or length, with soft and hard news, my pieces and interviews don't just inform but also engage - even entertain - their audience.

Of course, the number of folks aching to hear or read a story with tight-lipped and barely one-dimensional characters is exactly zero.

Luckily, my rarest personal and professional strength is an ingrained capacity for immediately establishing a genuine and weighty rapport with nearly all I meet, from U.S. presidents to inner city teens. This uncommon ability emboldens most every person I chat with to offer strikingly candid and commanding comments, regarding all subjects and situations.

Given my extraordinary interpersonal skills, it's no surprise I'm insatiably curious about the mindset and life experiences of everyone, not just my like-minded little coterie. I can probably best be described as a sort of cosmopolitan scout enthusiastically exploring the zeitgeist, able to identify and tap into shifting societal/cultural trends up close and personal.

Over the years, more than a few colleagues and radio listeners have compared my "ability to get inside the soul of someone" to Dostoevsky. Of course I would never be so wildly grandiose to liken myself to one of the greatest psychologists in world literature, please trust that certainty. I'm just the messenger, don't shoot.

Again, I hope you have a grand time Corey reading my profiles, they were great fun to research and write! <big smile>

Which is why I've always characterized myself professionally as a driven storyteller, versus a lazy fact-giver. An award-winning journalist unwilling to bore with easily composed but uninspired writing. No matter the topic or length, with soft and hard news, my pieces and interviews don't just inform but also engage - even entertain - their audience.

Of course, the number of folks aching to hear or read a story with tight-lipped and barely one-dimensional characters is exactly zero.

Luckily, my rarest personal and professional strength is an ingrained capacity for immediately establishing a genuine and weighty rapport with nearly all I meet, from U.S. presidents to inner city teens. This uncommon ability emboldens most every person I chat with to offer strikingly candid and commanding comments, regarding all subjects and situations.

Given my extraordinary interpersonal skills, it's no surprise I'm insatiably curious about the mindset and life experiences of everyone, not just my like-minded little coterie. I can probably best be described as a sort of cosmopolitan scout enthusiastically exploring the zeitgeist, able to identify and tap into shifting societal/cultural trends up close and personal.

Over the years, more than a few colleagues and radio listeners have compared my "ability to get inside the soul of someone" to Dostoevsky. Of course I would never be so wildly grandiose to liken myself to one of the greatest psychologists in world literature, please trust that certainty. I'm just the messenger, don't shoot.

Again, I hope you have a grand time Corey reading my profiles, they were great fun to research and write! <big smile>

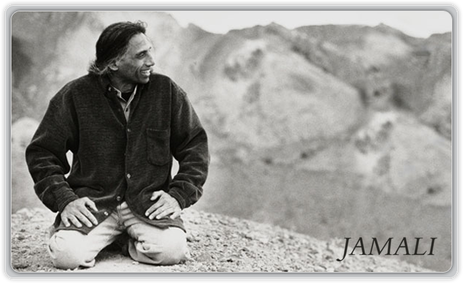

On Exhibit, Jamali: Artist, Guru, Marketing Maestro

Florida-based painter Jamali is a puzzling but perfect fusion of the Dalai Lama, Batman's the Riddler, and international pop star Madonna.

By Christopher Hosken

"In the beginning," lifting the opening of the Genesis creation narrative to launch Jamali's story, his mother living in Pakistan had a prophetic dream.

According to Jamali, she was visited in her sleep by a Buddhist monk who told her she would soon conceive a son with a very special task to perform.

He says he still remembers being two or three years old when a monk came to visit his mother and Jamali was brought outside. "They had conversation and he said this is the child. If you remember, I came in your dream? And she said yes, I remember."

Then, Jamali says, the monk said he would not return but told his mother Jamali "is going to have very strange and unique experiences but have no fear," adding "he will survive all of that and go ahead and do that job."

From kindergarten on, Jamali excelled at sports as well as academics. While at university he studied the sciences, with a focus on chemistry and physics. It had all come so easy to him, since Jamali was a child, and his future professional path felt obvious and even predestined.

Shocking to all, especially Jamali, he was totally mistaken. And not just a little bit.

Florida-based painter Jamali is a puzzling but perfect fusion of the Dalai Lama, Batman's the Riddler, and international pop star Madonna.

By Christopher Hosken

"In the beginning," lifting the opening of the Genesis creation narrative to launch Jamali's story, his mother living in Pakistan had a prophetic dream.

According to Jamali, she was visited in her sleep by a Buddhist monk who told her she would soon conceive a son with a very special task to perform.

He says he still remembers being two or three years old when a monk came to visit his mother and Jamali was brought outside. "They had conversation and he said this is the child. If you remember, I came in your dream? And she said yes, I remember."

Then, Jamali says, the monk said he would not return but told his mother Jamali "is going to have very strange and unique experiences but have no fear," adding "he will survive all of that and go ahead and do that job."

From kindergarten on, Jamali excelled at sports as well as academics. While at university he studied the sciences, with a focus on chemistry and physics. It had all come so easy to him, since Jamali was a child, and his future professional path felt obvious and even predestined.

Shocking to all, especially Jamali, he was totally mistaken. And not just a little bit.

During his 20s, Jamali suffered the sudden loss of his father. Like his mother, seven days after his father died, Jamali had a prophetic dream of his own. In it, he was given a lengthy poem. After waking, Jamali remembered the poem verbatim and scribbled it down. This pattern continued for weeks.

"The fortieth day after my father passed away, I had this dream in which this mystic came. He looked me straight in my eyes and pointed his finger at me and said, I have given you a task."

"That's it, Jamali lightly chuckles. "I started painting."

And doing so at a frenzied pace, creating more than 20-thousand paintings so far. Ask Jamali and he'll tell you he's on a divine mission.

This is where telling Jamali's already fantastical story becomes wildly complicated.

It's impossible to discuss his artwork without detailing Jamali's incredibly complex spiritual beliefs. You can chat with him about the topic for hours and still come away feeling with Luke Skywalker struggling to comprehend Yoda's riddles.

Employing Yoda speak. Confusing Jamali is, but try to explain I will.

"The fortieth day after my father passed away, I had this dream in which this mystic came. He looked me straight in my eyes and pointed his finger at me and said, I have given you a task."

"That's it, Jamali lightly chuckles. "I started painting."

And doing so at a frenzied pace, creating more than 20-thousand paintings so far. Ask Jamali and he'll tell you he's on a divine mission.

This is where telling Jamali's already fantastical story becomes wildly complicated.

It's impossible to discuss his artwork without detailing Jamali's incredibly complex spiritual beliefs. You can chat with him about the topic for hours and still come away feeling with Luke Skywalker struggling to comprehend Yoda's riddles.

Employing Yoda speak. Confusing Jamali is, but try to explain I will.

Both personally and professionally, Jamali rejects being categorized or identified with any of the world's major religions. However he admits he and his work are influenced by select bits plucked from Buddhism, Judaism, and Christianity. And Jamali fully embraces the characterization as a non-traditional Sufi, not bound by any particular Islamic teaching.

As a painter, Jamali is a self-described "mystical expressionist" who asserts he's the first artist ever to merge abstraction with God.

What to say about such a dazzlingly bombastic claim? I'm sure I don't know.

Here's how he works.

First picture someone wearing a cloth spacesuit with a gas mask instead of a helmet.

His canvas? A giant piece of cork about the size of small bedroom, with waist-high tree branches everywhere, surrounded on all sides by jars of wet and powdered paint.

Now envision Jamali atop this huge debris-covered surface scattering dry pigments, armed with a spray gun, occasionally picking up a smashed tree limb to etch something into the painting.

As a painter, Jamali is a self-described "mystical expressionist" who asserts he's the first artist ever to merge abstraction with God.

What to say about such a dazzlingly bombastic claim? I'm sure I don't know.

Here's how he works.

First picture someone wearing a cloth spacesuit with a gas mask instead of a helmet.

His canvas? A giant piece of cork about the size of small bedroom, with waist-high tree branches everywhere, surrounded on all sides by jars of wet and powdered paint.

Now envision Jamali atop this huge debris-covered surface scattering dry pigments, armed with a spray gun, occasionally picking up a smashed tree limb to etch something into the painting.

Throughout all this, his feet are in constant motion. Jamali says his movements, or "dance," are reenactments of dreams he had the previous night.

"These are ancient dreams," he says. "Mystics, prophets, and poets all had these dreams 10,000 years ago."

"Painting has never been done like this before, ever, in the history of man, says Jamali raising his voice. "Painters were afraid to go inside because they knew that painting is sacred, that the dance is sacred. You can't go inside."

"But I made that leap!"

"These are ancient dreams," he says. "Mystics, prophets, and poets all had these dreams 10,000 years ago."

"Painting has never been done like this before, ever, in the history of man, says Jamali raising his voice. "Painters were afraid to go inside because they knew that painting is sacred, that the dance is sacred. You can't go inside."

"But I made that leap!"

Winston Churchill could just as well been describing Jamali instead of Russia when he called it "a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma."

Jamali can be breathtakingly grandiose one minute, radiating humility and compassion the next. Distant at times, irresistibly likable most others. An artist that seems forever and only passionate about his work, but then there's the super shrewd image marketing maestro.

When talking to Jamali you notice all these things all at once, just take a listen to a brief portion of our interview.

Jamali can be breathtakingly grandiose one minute, radiating humility and compassion the next. Distant at times, irresistibly likable most others. An artist that seems forever and only passionate about his work, but then there's the super shrewd image marketing maestro.

When talking to Jamali you notice all these things all at once, just take a listen to a brief portion of our interview.

Christopher Hosken

Tags: Jamali, mystical expressionism, abstract artist, Orlando, God, spirituality, art

Jamali Links & Video

In addition to visiting Jamali's official website where you can also see his sculpture, below is part of a documentary about the artist, plus a trio of dreamy video portraits of his work.

|

|

|

|

|

|

This piece was originally part of the award-winning “Do No Harm” radio series. The project included five hour-long segments investigating critical topics in the field of medical ethics and was broadcast on hundreds of National Public Radio member stations around the country.

My story was in the hour titled “Treatment and Trials: Balancing the Risks and Benefits” and bookended by an interview with the director of Duke University’s Center for the Study of Medical Ethics and Humanities.

Since all troubles were addressed by the center's director, my journalistic mission didn’t necessitate detailing the center's numerous high-profile ethics scandals and forced human research shutdown etc. In narrative fashion, I simply introduce you to a pair of self-described “guinea pigs” that describe what it's like to take part in research studies and why they volunteer.

My story was in the hour titled “Treatment and Trials: Balancing the Risks and Benefits” and bookended by an interview with the director of Duke University’s Center for the Study of Medical Ethics and Humanities.

Since all troubles were addressed by the center's director, my journalistic mission didn’t necessitate detailing the center's numerous high-profile ethics scandals and forced human research shutdown etc. In narrative fashion, I simply introduce you to a pair of self-described “guinea pigs” that describe what it's like to take part in research studies and why they volunteer.

As well as personal accounts of research volunteers, Guinea Pig Zero contains advice and reviews of test clinics.

As well as personal accounts of research volunteers, Guinea Pig Zero contains advice and reviews of test clinics.

Under the Microscope, Human Research Volunteers

Self-described “guinea pigs” fiercely complete for experimental clinical trials that can last years, require miserable in-lab lock-downs, with no guarantee against side effects.

By Christopher Hosken

You owe a lot to human guinea pigs.

We all do, for the countless wonder drugs and miracle surgical procedures available today. Someone had to be the first to try them out, test for adverse reactions, and make sure they were safe.

This is how it has worked the entire history of medical research.

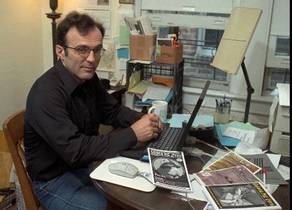

Robert Helms, a 44-year-old longtime “lab rat” who publishes the zine Guinea Pig Zero, says death row inmates were often used during the Renaissance as practice models for surgery. He details one example where the king of France was injured in a joust.

“He had a lance through the eyeball and it ran into the back of his head.” Helms says the king was dying, so convicted felons were brought in. “And they would just carve into their heads,” he says, “or stab them with a similar piece of wood as practice before trying it on the king.”

Since one could be sentenced to death back then for stealing a loaf of bread, many of these eventual test subjects were poor.

Centuries later, Helms says it is still mainly low income individuals volunteering for experimental research studies.

“I do this for the money, not because it’ll help humanity,” he says bluntly. “And most people who do what I do, it’s for their own good.”

Self-described “guinea pigs” fiercely complete for experimental clinical trials that can last years, require miserable in-lab lock-downs, with no guarantee against side effects.

By Christopher Hosken

You owe a lot to human guinea pigs.

We all do, for the countless wonder drugs and miracle surgical procedures available today. Someone had to be the first to try them out, test for adverse reactions, and make sure they were safe.

This is how it has worked the entire history of medical research.

Robert Helms, a 44-year-old longtime “lab rat” who publishes the zine Guinea Pig Zero, says death row inmates were often used during the Renaissance as practice models for surgery. He details one example where the king of France was injured in a joust.

“He had a lance through the eyeball and it ran into the back of his head.” Helms says the king was dying, so convicted felons were brought in. “And they would just carve into their heads,” he says, “or stab them with a similar piece of wood as practice before trying it on the king.”

Since one could be sentenced to death back then for stealing a loaf of bread, many of these eventual test subjects were poor.

Centuries later, Helms says it is still mainly low income individuals volunteering for experimental research studies.

“I do this for the money, not because it’ll help humanity,” he says bluntly. “And most people who do what I do, it’s for their own good.”

Robert Helms inside the Philadelphia apartment where he creates his zine.

Robert Helms inside the Philadelphia apartment where he creates his zine.

Helms differs sharply though from from the majority of his fellow research subjects when it comes to the type of experiments he'll do.

Thanks to an "uncommon concern" for his own safety, unlike so many other clinical trial participants, Helms is adamant he has never signed up for any experiment involving psychiatric drugs.

"My idea of it is I'm renting out my body and not my brain."

Despite some studies awarding participants thousands of dollars, most volunteers quit after just one or two studies. But the less squeamish, unworried about potential side effects, view clinical trials as easy money.

The majority do them part-time, but some make a career chasing the next study from state to state living out of a duffle bag. In the trade, these mostly male nomads are referred to as "gypsy guinea pigs." The Triangle is one of their top destinations with so many clinical trials conducted at area universities and private labs.

Sharon has taken part in many of those trials, for everything from a long-term AIDS study needing healthy volunteers, to a recent one testing support pantyhose for people with poor circulation.

Thanks to an "uncommon concern" for his own safety, unlike so many other clinical trial participants, Helms is adamant he has never signed up for any experiment involving psychiatric drugs.

"My idea of it is I'm renting out my body and not my brain."

Despite some studies awarding participants thousands of dollars, most volunteers quit after just one or two studies. But the less squeamish, unworried about potential side effects, view clinical trials as easy money.

The majority do them part-time, but some make a career chasing the next study from state to state living out of a duffle bag. In the trade, these mostly male nomads are referred to as "gypsy guinea pigs." The Triangle is one of their top destinations with so many clinical trials conducted at area universities and private labs.

Sharon has taken part in many of those trials, for everything from a long-term AIDS study needing healthy volunteers, to a recent one testing support pantyhose for people with poor circulation.

"I think they just wanted to see when I'd probably pass out and fall off the bicycle," says a Triangle area veteran volunteer.

Aware of the stigma, plus possible retaliation by local companies and researchers, this 49-year-old mother of three asked that her last name not be mentioned. To pay the bills, Sharon is a substitute teacher and occasional house painter who has been doing research studies for the past seven years.

"During that time, I've likely given about five gallons of blood, along with other bodily fluids. I have probably taken enough capsules, pills, and liquids to fill the back of a large pickup truck." She rolls her eyes while also recalling "numerous x-rays and other invasive tests, plus lots and lots and lots of paperwork."

At the beginning of each year, Sharon sits down with a calendar and plots out the number of clinical studies she can squeeze in. Usually it is about four or five.

"During that time, I've likely given about five gallons of blood, along with other bodily fluids. I have probably taken enough capsules, pills, and liquids to fill the back of a large pickup truck." She rolls her eyes while also recalling "numerous x-rays and other invasive tests, plus lots and lots and lots of paperwork."

At the beginning of each year, Sharon sits down with a calendar and plots out the number of clinical studies she can squeeze in. Usually it is about four or five.

“All the professional guinea pigs are looking for the high-dollar studies, so you have to start calling the research centers as soon as you find one or they’ll fill up. It gets almost cutthroat.” To comply with each trial’s requirements, Sharon says people will go on severe crash diets, “and if you’re taking medications the study doesn’t allow, you better quit taking them real quick.”

While others are regularly trying to speedily flush their bodies to pass the required drug screens, Sharon swears the diverse compliance requirements are not a problem. In fact, she compares herself to an athlete always trying to eat well and stay in shape to remain an attractive candidate for researchers needing healthy human subjects.

She points to one unforgettable study focused on exercise physiology.

"I had to peddle a bicycle with all kinds of tubes and electrical nodes attached to me." The researchers would ramp up the bike speed while slowly decreasing her oxygen. "I think they just wanted to see when I'd probably pass out and fall off the bicycle."

Most of the studies she competes for aren't so physically demanding, with only a few requiring overnight stays at a university hospital or private research lab.

"Just knowing you weren’t allowed out and locked inside. It was almost like the nurses were prison guards," says Sharon.

The culture/entertainment site gabWorthy listed human research one of Nine Science Professions That Are Wacky And Unpopular.

The culture/entertainment site gabWorthy listed human research one of Nine Science Professions That Are Wacky And Unpopular.

Years later, Sharon still winces while describing one clinical trial that required multiple weekend lock-downs.

All would check in each Friday afternoon. Bags were immediately searched, then numbers were drawn for bunk assignments with men on one side and women on the other.

At certain times each day, blood was taken and medication given. Like you see in the movies, nurses made people open their mouths to ensure they had swallowed their meds. The blood draws were done three times a day.

The first night was unremarkable, but the second was always much worse.

“Some were climbing the walls, others were making sock dolls, or playing cards.” Sharon says all were mind-numbingly bored and stir-crazy. “Just knowing you weren’t allowed out and locked inside. It was almost like the nurses were prison guards.”

“We lost a couple of the men because they couldn’t handle all the blood sticks,” Sharon chuckles. In total, each volunteer endured 57 blood draws. "My vein on my left arm was very tired of looking at needles and trying shutdown during the very last draws, but I was glad when it was done.”

“Ten days later I got my check in the mail,” she says with a look of pride and achievement in her eyes.

She used the $1,500 to catch-up on her car payments.

All would check in each Friday afternoon. Bags were immediately searched, then numbers were drawn for bunk assignments with men on one side and women on the other.

At certain times each day, blood was taken and medication given. Like you see in the movies, nurses made people open their mouths to ensure they had swallowed their meds. The blood draws were done three times a day.

The first night was unremarkable, but the second was always much worse.

“Some were climbing the walls, others were making sock dolls, or playing cards.” Sharon says all were mind-numbingly bored and stir-crazy. “Just knowing you weren’t allowed out and locked inside. It was almost like the nurses were prison guards.”

“We lost a couple of the men because they couldn’t handle all the blood sticks,” Sharon chuckles. In total, each volunteer endured 57 blood draws. "My vein on my left arm was very tired of looking at needles and trying shutdown during the very last draws, but I was glad when it was done.”

“Ten days later I got my check in the mail,” she says with a look of pride and achievement in her eyes.

She used the $1,500 to catch-up on her car payments.

“My body is the only thing that really matters to the experimenter. It’s the same as when a prostitute takes on a customer," says Robert Helms.

"My mother thinks it's gross," Sharon admits.

Her husband also protests the research studies as "dark and sleazy," but she thinks he's just worried about her safety.

Fellow volunteer Robert Helms argues human research subject is much like the sex trade because there is bodily penetration.

“An invasion of privacy is involved that most people would find unacceptable.” Helms also points out that emotional feelings, opinions, and thoughts are not considered. “My body is the only thing that really matters to the experimenter,” adding “it’s the same as when a prostitute takes on a customer.”

Sharon says she couldn't agree less with Helms. "I consider it like any other part-time job," she states sternly. "It's money coming in the house."

Despite any social stigma or criticism from family members, Sharon asserts she is undeterred and promises to continue as long as she can fit the researchers’ criteria.

Christopher Hosken

Her husband also protests the research studies as "dark and sleazy," but she thinks he's just worried about her safety.

Fellow volunteer Robert Helms argues human research subject is much like the sex trade because there is bodily penetration.

“An invasion of privacy is involved that most people would find unacceptable.” Helms also points out that emotional feelings, opinions, and thoughts are not considered. “My body is the only thing that really matters to the experimenter,” adding “it’s the same as when a prostitute takes on a customer.”

Sharon says she couldn't agree less with Helms. "I consider it like any other part-time job," she states sternly. "It's money coming in the house."

Despite any social stigma or criticism from family members, Sharon asserts she is undeterred and promises to continue as long as she can fit the researchers’ criteria.

Christopher Hosken

Tags: human research, guinea pigs, research studies, Robert Helms, lab rats, clinical trials, experimental treatments

Related Video

Here are a trio of sound clips from Guinea Pig Zero's longtime publisher Robert Helms. These were plucked from a relatively recent documentary Control Group did about human research subjects. Helms sometimes refers to past experiences because he decided years ago to continue with the zine but stop doing clinical trials.

Time for me to wave so long, farewell.

Before I go allow me to inform you I began my career as a print journalist, plus point out the obvious, that all the radio pieces I've ever voiced were first scripts with some posted on NPR station websites for visitors to read.

Finally, I extend an enthusiastic invitation Corey to peruse the rest of my site for a more expansive sampling of my reportage. Like my main GREETINGS page details, I'm in the process now of totally revamping most everything on this site and much will be rearranged with new content added, including entirely reimagined individual story descriptions.

All that's left to say, and sing, is....